Brewery to Bakery: Can Bakers Adopt Beer Making Technology to Improve Their Bread?

by Eric Ferias

When the process of microbial fermentation was discovered, both bakers and brewers were gifted a roadmap from nature to configure high-quality products. While the brewing industry has taken a massive step in the last hundred years by harnessing new microbial technologies to perfect beer production, the bread industry has not experienced the same renaissance.

Bread and beer have similar ancient origins; both use the harvesting of excess grains, an abundant access to water and require fermentation. These ancient fermentations carried out by a spontaneous set of yeast and bacteria, known to fermenters in the Middle Ages as “Godisgood”, were often shared between beer and bread.

Methodologies used for these fermentations remained relatively unchanged until Louis Pasteur described the processes of lactic acid fermentation (1857) and alcohol fermentation (1858). Pasture’s revelations led to the isolation of pure strains of yeast and bacteria which, at the turn of the century, were developed into concentrated products for leavening dough or making beer at the scales needed to provide for a rapidly expanding population.

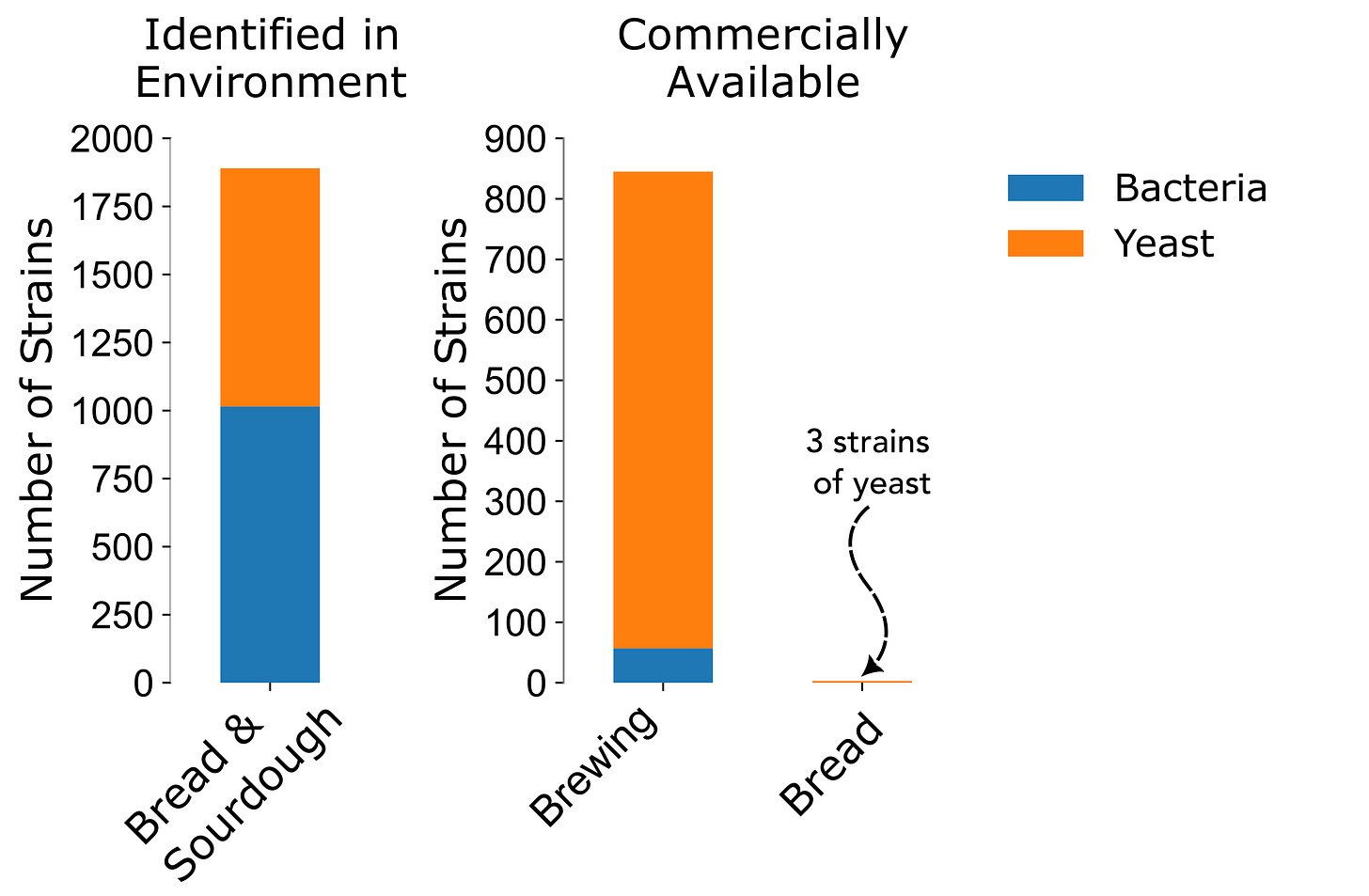

Since that time, many other strains of bacteria & yeast have been made available for beer manufacturing, allowing for a large variety of beer to be produced in a single facility. Breadmaking has yet to experience this boon of microbial innovation. Currently, bakers have two options, a sourdough starter at a small scale, or the same yeast isolated by Pasture in the 1800s used at a large scale.

In part, microbes might have received extra attention in the brewing world due to the oversized effect that they play in the flavor and aroma of the end product. It was recognized that some breweries and regions created beer with unique sensory qualities compared to others using similar ingredients and processes. One explanation for the differing attributes was that “house” microbes were responsible for imparting unique traits to the beer.

Unlike baked goods, flavor and aromatic compounds in beer aren’t evaporated during baking. Therefore, any unwanted flavor or aroma contributions from microbes will be reflected in the final beer. As brewers worldwide desired to recreate beer styles from their favorite locations and breweries, exploration and use of starter cultures from all over the globe gained traction.

The understanding of the microbial contribution to sensory attributes coupled with the desire to brew “clean” beers (those free from off flavors) and eclectic styles led to the advent of strain collection companies that collect and study the properties of brewing cultures. These companies supply the majority of starter cultures used in the brewing industry and offer a well-defined, quality-controlled source for microbes which gives brewers the option to create an array of beer styles.

Another possible explanation for the acceleration of brewing starter culture development was the medium in which beer-making takes place. Liquid medium of brewing parallels the methods in which microbiologists grow and study microbes, allowing for an easier transfer of knowledge compared to dough. This process similarity allowed brewers to take concepts directly from diverse scientific literature and directly apply them to the brewing process.

So, what can bakers do to control their dough in the same way a brewer can control their beer fermentation? Well, here at Leaven, we are trying to solve this problem by studying the relationship between yeast and bacterial strains found naturally in sourdough to improve baked goods. We are inspired by the idea of giving bakers the ability to match the level of sophistication of their sister craft, beer.

If you are interested in hearing more about this topic from the perspective of a brewer, check out this video (below) of expert brewer Jon Porter in conversation with the dough whisperer Noel Brohner and Leaven’s Founder Cameron Martino.